“THE Middle East has oil. China has rare earth metals.” So said Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s post-Maoist opening and rise, in the 1980s, with remarkable foresight and precision. The rest of the world is only now grasping the implications of his insight for geopolitics in the 21st century.

The natural resource that shaped world politics in the long 20th century — which, for these purposes, started in the late 19th and hasn’t quite ended yet — has been oil. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, they were — at least as they saw it — reacting to a Western oil embargo on them. When Adolf Hitler sent the Wehrmacht to Stalingrad, he was eyeing the black gold of the Caucasus. When the Americans started holding hands with the House of Saud, they were after the crude of Arabia and the wider Middle East. Oil shocks, Iraq wars, and any number of other events have kept reminding the world that much of its economic, diplomatic, and political superstructure has been based on the substructure of this hydrocarbon.

World leaders who — in contrast to Deng — look backwards in time have tended to draw the wrong conclusions from this history. Russian President Vladimir Putin has built his own rise during the 21st century on the assumption that he could turn Russia from a petrostate into a superpower that’s simultaneously his personal fief. For decades he laid pipelines for Russian oil and gas with the intention of making countries from Ukraine to Germany dependent on these flows, and thus subject to his geopolitical blackmail. A year into his attack on Ukraine, it appears that he miscalculated.

The Chinese, since the 1980s, have followed a different strategy, mining those rare earths Deng was talking about. They include 17 elements most ordinary people have never heard of, and could barely find on the Periodic Table — in part because 15 of them, the so-called lanthanides, are banished to their own exclave on the chart. They have exotic names — ytterbium, erbium, praseodymium, neodymium, samarium, dysprosium — that sound like the cast of villains in a bad Star Wars sequel.

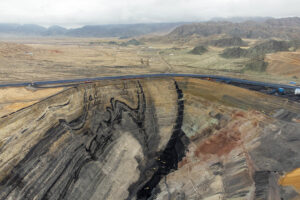

Despite their label, these “earths” are not actually all that rare. Some, such as cerium, are more abundant than copper or lead, and even one of the scarcest, thulium, is more common than gold. But they’re much harder to mine, because they tend to be spread out in their ores. Building the infrastructure to get them out of the ground and apart from other rock takes decades. Even then, the process is expensive, messy, and bad for the environment.

China, starting with Deng, decided to tolerate all of this. It has about a third of the world’s deposits, most of them in one gigantic lode in Inner Mongolia. Patiently investing in all parts of the production process, it displaced the former market leader, the US, in the 1990s. By 2010, China in effect had a global monopoly on supply, with market shares above 90%.

That rang alarm bells in Western capitals. Rare earths are used in everything from fiber optics and lasers to medical scanners and the hard discs in our computers — they’re the building blocks of the modern world. They’re also inside state-of-the-art weapons systems, and thus a prerequisite to military prowess. Each American F-35 fighter plane, for example, contains about 920 pounds of rare earths.

Above all, some of the 17 elements are crucial for success in the coming green revolution. To phase out fossil fuels — that is, to exit the era of oil, gas, and coal — we need to harness vastly more energy from wind and use the resulting electricity to power our cars and trucks. But turbines and electric vehicles run on super magnets made in part from praseodymium, neodymium, samarium, and dysprosium.

A rare-earth shock, therefore, could in the 21st century kneecap economies, armies, and countries as much as — or more than — the oil shocks of the 1970s did. Beijing knows and likes that prospect. In 2010, after the Japanese detained a Chinese trawler that had sailed through a disputed island group, China halted all rare-earth exports to Japan until Tokyo set the boat free. A decade later, after the US offered Taiwan a defense deal, Beijing threatened to stop supplying Lockheed Martin, the maker of the F-35, and other American companies.

The good news is that the penny has dropped and more countries are now trying hard to unearth their own supplies and diversify away from China. The US is back in the business, as are Australia, Myanmar, Canada and others. Japan has discovered a huge lode, although it’s under the sea bed and hard to get to. Turkey has found its own trove in central Anatolia. But building the infrastructure and know-how takes years.

While China’s market share in rare earths is trending down, it’s still huge — amounting to 60% of world extraction as of 2019, and 87% of processing. From the US to the European Union, governments are working on adding new supply chains. Countries like Germany, still smarting from its naive submission to Putin’s pipeline diplomacy, are reconsidering their reliance on China.

As well they should. Now that Putin, as part of his barbaric assault against Ukraine and decency in general, has declared energy war on the West, it seems prudent not to stumble right into the next dependency on an autocratic regime with irredentist grudges. As Western spooks like to say, “Russia is the storm, China is climate change.” The 21st century is young. It would be a pity if we allowed rare earths to do to it what oil did to the 20th.

BLOOMBERG OPINION