PhilHealth members still pay out of pocket in spite of universal healthcare, according to a group of researchers from the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS). They said, “Despite modest improvements in health outcomes, inequities continue to exist due to unresolved challenges in access to healthcare. This includes the physical constraints due to lack of health facilities along with the financial risks of catastrophic expenses especially for vulnerable population.” The elderly, women, rural, and poor Filipinos are more likely to spend more with the national health insurance coverage limited to 40% of total hospital costs, the researchers added.

PhilHealth members will be paying out of pocket for 60% of their hospital bill in the next so many years because universal healthcare is not yet in place in the country. In this age of advanced medical science, of miracle drugs, invasive surgeries, and organ transplants there would be financial risks for catastrophic expenses. Your wealth or your health is an issue confronting many. Universal healthcare (UHC) was not conceived for them.

UHC was meant for people whose lives can be saved or whose good health can be maintained if they receive timely medical attention without ruining them financially. Complications of the leading diseases in the Philippines like bronchitis, influenza, chicken pox, diarrhea, and respiratory tract infection can be prevented if the patient receives preventive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative health services.

To achieve the goal of UHC, the country must have a strong, efficient, well-run health system that meets priority health needs, access to essential medicines and technologies to diagnose and treat medical problems, and a large corps of trained, motivated health workers to provide the services patients need.

The World Health Organization (WHO) had advised our legislators to implement universal healthcare fully in 2030 when the country’s health delivery system would be capable of servicing UHC. But some of them rushed the enactment of a law instituting universal healthcare, RA 11223, so that they could present UHC in the elections of 2019 as their gift to the Filipino people. Among the authors of the law were Senators JV Ejercito, Sonny Angara, Nancy Binay, and Cynthia Villar, who were all running for re-election. Ironically, only JV Ejercito, the principal author of the law, failed to be re-elected.

Republic Act No. 11223 mandated that all Filipinos get the healthcare they need, when they need it, without getting impoverished. The law enrolled all Filipino citizens in the National Health Insurance Program to be administered by the Philippine Health Insurance Corp. or PhilHealth. That is 112 million Filipinos spread all over the archipelago — from Batanes in the north to Jolo in the South, from Samar in the East to Palawan in the West.

As the WHO feared, the country’s health system is far from being capable of servicing UHC. The United Kingdom owns the hospitals and employs the healthcare workers that service all its citizens. While the Philippine government also owns hospitals and employs healthcare workers, their number falls way short of those required to provide the health services needed by the 112 million Filipinos insured with PhilHealth.

According to the Department of Health (DoH), as of 2022 there are 721 public hospitals, 66 of which are managed by the DoH while the remaining hospitals are managed by LGUs and other National Government agencies. Government hospitals do not provide adequate medical care. Like Hospital ng Manila, they provide accommodations and professional health services to the sick, but not the drugs and medicine.

Both public and private hospitals are classified by their service capability. Level 1 hospitals are staffed by specialists in family medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics-gynecology, and surgery. Level 2 hospitals have all Level 1 specialists plus departmental clinical services, respiratory unit, general ICU, high-risk pregnancy unit, and dental clinic. Level 3 hospitals, commonly referred to as general hospitals, have all of Levels 1 and 2 physicians plus teaching/training with at least two accredited residency programs for physicians in any medical/surgical specialty and/or subspecialty, physical medicine and rehabilitation unit, ambulatory surgical clinic, and dialysis clinic.

The number of hospital beds is a good indicator of health service availability. Per WHO recommendation, there should be 20 hospital beds per 10,000 population. Almost all regions in the country have insufficient beds relative to the population. The insufficiency of public hospital beds is unspeakable. The table below shows the pathetic situation with regard to DoH managed hospitals.

A 108% occupancy rate means there are more inpatients in the hospital than there are beds available. Some inpatients are made to lie on benches in waiting areas, others just have to be treated on visitor chairs. There are instances when two patients share a bed. Such instances occur during the dengue season, when many of those infected are children.

So, many patients are turned away. Poor folks denied admission just go home to their shack or hut, treat themselves with herbal remedies or consult the neighborhood arbolaryo (folk doctor). The Philippine General Hospital had refused hundreds of COVID-19 patients at the height of the pandemic such that when President Duterte’s spokesperson Harry Roque got admitted into the hospital immediately after he got afflicted with the disease, the hospital’s administrator found himself confronted with a colossal political issue.

With the public hospitals overcrowded, income earners seek medical attention in private hospitals. Most of them were established for profit. Their payment system is independent of the strict guidelines observed in government-owned hospitals. As the physician-stockholder of private hospitals enjoys full discretion in using the hospital’s facilities, his practice is influenced by the incentives available to him.

He may recommend diagnostic tests, longer hospital confinements, and surgeries much more than necessary. For every procedure, for every service, the physician charges a fee. Depending on the doctor’s assessment of the patient’s capacity to pay, he may even order high-tech diagnostic tests the equipment for which he owns and which is right in his office. He prescribes the newest and therefore more expensive medicine for which act he is rewarded by the manufacturer with a fully-paid-for vacation abroad disguised as attendance of a medical convention.

A number of medical directors of non-profit and philanthropic medical institutions in the US have said much of the waste and excess utilization that take place in laboratory, radiology, and pharmacy may be unnecessary and even potentially dangerous. The extra but unnecessary services and wonder drugs account for the findings of the PIDS researchers — that PhilHealth members pay out of pocket for 60% of their hospital bill.

Government-owned specialty hospitals are going to get a bigger budget this year — as much as P7 billion, P1 billion more than last year. These are the Philippine Heart Center, the Lung Center of the Philippines, the National Kidney and Transplant Institute, the Philippine Children’s Medical Center, and the Philippine Institute of Traditional Alternative Health Care. All five medical facilities are located in Metro Manila.

In many parts of the country, farm workers, market vendors, food stall operators, tricycle/jeepney drivers, and retail store attendants who fall ill do not get the proper medical attention due mainly to the inaccessibility of a healthcare facility. It is time the government provided the folks in the countryside healthcare.

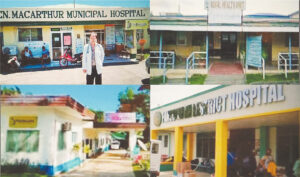

Now that JV Ejercito, the principal author of the Universal Health Care Act, has been elected again to the Senate, he and Sonny Angara, Nancy Binay, and Cynthia Villar, who owe their re-election to the Senate in 2019 mainly to their being signatories to that Act, should push for the enactment of a law that will mandate the establishment of more healthcare facilities in the countryside to make universal healthcare in the Philippines a reality. The facilities need not be all Level 3 hospitals. A large number can be modest Level 1 units. At least one Level 1 facility like the ones shown here should be put up in every congressional district.

Oscar P. Lagman, Jr. is a retired corporate executive, business consultant, and management professor.