For 2025, I wish my friend and erstwhile colleague at the University of the Philippines Diliman School of Economics (UPSE) and currently at National Academy of Science and Technology, Philippines (NAST Phil.), the Secretary Arsenio Balisacan, a realization, a most cherished hope: the attainment of the upper middle-income status for the Philippines. Reaching the $4,516/capita GDP to cap the year just passed 2024, is a cherished wish of the Planning Secretary and of the whole nation. The upper middle-income standard ranges from $4,516 to $14,005 per capita. For us seniors where I belong, the middle-income range starts at $10,000 and ends at $15,000/capita, but that is now old school.

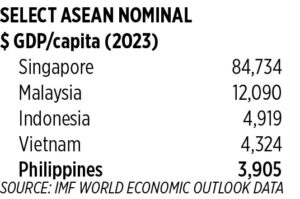

A table on the Asean nominal GDP per capita for select Asean countries in 2023 accompanies this piece for context.

The Philippines’ GDP/capita remains below $4,000/capita and below upper middle-income country standard in this list. We used to have Indonesia and Vietnam in our rear-view mirror.

Our per capita income in 2023 being $3,905/capita by IMF reckoning is a standout for the wrong reason. The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) estimate is higher at $4,230/capita. By PSA reckoning, the Philippine economy needs to grow only 6.7% for all of 2024 to reach $4,516 per capita at the start of 2025. A cakewalk you say? But by the IMF estimate, the GDP growth rate required to graduate from the lower middle-income level is 15.6%, and will take two or three years to attain. But, even the growth rate of 6.7% seems an already difficult attainment.

The GDP growth rate was only 5.6% in 2023 after the disappearance of the pandemic-related low base effect; this was down from the post-pandemic low base effect growth bubble of 7.6% in 2022. This low base effect may still figure in 2024 and may result in growth in the vicinity of 5%, especially after the climate disturbances and floods in H1 2024 are accounted for. Portent of this is the growth in Q3 2024 being only 5.2% and below the 6% growth in Q3 2023.

By the IMF reckoning, we may need to wait to 2025 or 2026 for the Rubicon to be crossed. We have, however, a long history of turning great growth prospects into muck. This happened in 1986-1990 and in 1997-2000. And now in early 2025, political storm clouds are stealthily gathering once more with the bad (nay, vicious) blood in the wake of the breakup of the dominant political coalition and the decidedly subversive language being hurled from the Southern faction. The military’s highest leadership has had to reaffirm its loyalty to the constitution on Jan. 4 in the wake of the restructuring of the National Security Council. This is a sign that there is potential trouble to be quelled. The economic team, and the nation with them, hope and pray that the military remains true to the constitutional authority. Otherwise, all bets are off.

If the graduation miraculously comes to pass in 2024-2025, it will do so with the Philippine economy hobbling with the same age-old problems: food insecurity will still threaten food inflation (tomatoes as of January are selling at P200/kilo); malnutrition and stunting among our young remains largely unaddressed; food importation remains the order on the policy front; we will still go begging in the international credit market to fill our import and other spending needs. Our investment rate (GDCF/GDPx100) will still be lowest in the ASEAN region, and our Government Capital Outlay still remains south of 8% of GDP standard among our fast-growing ASEAN neighbors. The Manufacturing sector still plays second fiddle to the buoyant Non-traded Goods sector. Our share in FDI relocating from Mainland China has budged little if at all while the whole global investment community is flocking to the new darling, Vietnam. None of these problems will resolve with our graduation to the upper middle-income country level.

I was in Jagna, Bohol, a port town, for a short traditional family Christmas reunion. The conversation is clearly about politics: the hearings in Congress are stirring new alliances, although local politics still leaning in favor of the southern faction dominates. Jagna Mayor Joseph Rañola declined to pursue his last term — a pity because while he succeeded in finding resources to backstop many worthwhile economic projects, rumor has that his disciplined governance has not endeared him to the voters who favor traditional back-slapping politicians who recall everyone’s name and who show up at every funeral. An instance perhaps of our thesis that in the Philippines, good politics trumps good economics!

Meanwhile, new cars and SUVs increasingly clog the narrow Jagna streets. SM Corp. finally broke ground on its mall in Tagbilaran City after being kept at bay by local politics and their local business alliance, led by the owners and operators of the sole Bohol Island City Mall. Jagna now has three formal banking branches: LANDBANK, Banco de Oro, and Metrobank. A 24-hour convenience shop has opened. But traditional retail (mercado) business in Jagna and small urban areas are barely surviving the competition from the digital outfits — Shopee and Lazada are taking over the market of upper income households with command of the 4G gadgets.

Whence is the local economic buoyancy? The upgrade of public school teacher wages and that of other government employees, thanks to the tail end of the salary standardization law, is contributive. The proceeds of the Mandanas-Garcia law are also contributive to the LGU’s project financing, though the LGUs are complaining that only 31% of their proper share of indirect taxes is being handed over. Another source of artificial prosperity is the ayuda (assistance) fund called AKAP or Ayuda sa Kapos ang Kita Program, sold as pro-poor but in reality, political payola amounting to P731 billion in 2023. All of these are, however, only reallocations of current resources and not the harvest of new investment.

The upward adjustment of public school teacher salaries has a worrying negative effect on private education in the country: many private secondary education establishments in the country are closing down because of their inability to match the salaries of teachers in public schools. This is true also of Bohol. The possible effect is the lowering of education standards, since private education institutions generally have higher standards having to compete with other schools for tuition-paying students. Despite the salary upgrade, the Department of Education is still unable or unwilling to release the results of national secondary school aptitude exams to ferret out the wheat from the chaff in secondary education.

The private education support of junior and senior high school students is what’s keeping the Central Visayas Institute Foundation (CVIF) viable by enabling it to compensate its teachers with salaries comparable to that of public teachers. CVIF is a very highly motivated secondary high school and is the pride of Jagna town, which has attracted many visitors from all over the country eager to learn its novel learning-by-doing pedagogy called the Dynamic Learning Program (DLP). Here is a solution to our learning poverty which was long-ignored by the national educational authorities saddled by business-as-usual practices. Other private institutions are unable to match the salaries of public school teachers and thus have had to close down.

To keep private secondary schools viable, the voucher system to support private enrollment must be expanded. But where to get the money? The government fiscal position seems precarious. A fiscal crisis may even be looming: the government debt has passed P15 trillion and the government is looking to borrow more. The government is scrambling to replenish the unprogrammed budget; the latter is easy to redirect for political purposes (such as the 50% reduction in the Philippine Deposit Insurance Corp. or PDIC reserve fund and the shortchanging in the share of LGUs in the Mandanas-Garcia fund). The government has allowed the siphoning off of P117 billion (50%) from the reserve of the PDIC, which is required to support the deposits in our banking system. The use of unprogrammed funds (P731 billion for ayuda in 2023) for political ends has been exposed as fraudulent.

Remarkable in its non-pursuit is one potential bright spot. The reform in the military pension which, by a Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) study, would reduce the unfunded liabilities to P2 trillion from P9 trillion per year for 20 years is one potential bright spot provided indexation is replaced by a 1.5% increase in retired military and uniformed personnel (MUP) pensions, a 21% increase in mandatory contributions by regular MUP, and compulsory retirement at 60 years old. This would reduce the fiscal burn from P848.4 billion to P208 billion annually for 20 years, but is still being kicked down the road. It will continue to disembowel our long-term fiscal stability. This is no longer viable as legislation with the military being asked by ex-president DU30 (Duterte) to save the nation from PBBM (President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr.).

So, shall the upbeat New Year’s prognostication of Secretary Arsenio Balisacan of the country finally entering the ranks of the upper middle-income come to pass in 2025? I hope and pray that it does. But the signs are not auspicious. Agriculture met a “perfect storm” in 2024 — droughts, pests and floods — according to the Agriculture Secretary. The investment rate remains below the 25% of GDP standard. The government capital outlay remains less than the 8% standard.

In other words, if we do cross the threshold, it will be on the strength of a wing and a prayer. But as an old song goes, “Miracles do come true, it can happen to you.”

Raul V. Fabella is a retired professor at the UP School of Economics, a member of the National Academy of Science and Technology, and an honorary professor at the Asian Institute of Management. He gets his dopamine fix from bicycling, assiduously if with little success courting the guitar, and tending lowers with his wife Teena.