Almost everyone who has ever picked up a video game controller will have played at least one Mario game. Whether you had a Nintendo Entertainment System in the 1980s, the N64 in the 90s or a Wii in the 00s, the joyful little jumping plumber has graced every generation of Nintendo’s consoles – and touched every generation of players. Over 373m Super Mario games have been sold to date, which means hundreds of millions of siblings uniting to find Star Road in Super Mario World, commuters escaping with Super Mario 3D Land on the train, and parents soaring from planet to planet in Super Mario Galaxy with their kids.

These are in essence straightforward games about the pleasure of running and jumping, of moving a character around in colourful, abstract space. What makes them better than a thousand other platformers, as this genre is known, is the finesse and responsiveness in Mario’s movement. The soaring jump, the slight inertia that carries him forward after a leap, and the sudden acceleration of his run all translate to pleasure when you play. There is such skill and satisfaction in mastering his movement, in stringing together backflips and wall-kicks and long-jumps to scale the geometry of the levels and find their secrets, and this is what has enthralled children (and adults) for 35 years. Mario’s designers know to hide things in the nooks and crannies of these levels, to always answer the question “what happens when I do this?” with “something fun”.

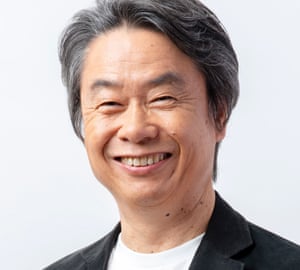

The first of those designers, Shigeru Miyamoto, was 24 years old when he joined Nintendo in 1977, and a month shy of his 33rd birthday when the original Super Mario Bros was released. For him, that joy of movement is what still defines Mario, even as he has gone from little pixel-man to galaxy-hopping superstar. “[Mario is about] being able to feel yourself improve to the extent that you learn the moves by heart, and then using those moves, thinking about what to do next and trying different things out. Creating all kinds of different reactions to this player experimentation has been the core of these games,” he says. “I’ve [always] felt that players trying out different things, knowing full well what it is that they are doing, is the core of interactive gameplay.”

Takashi Tezuka, who worked alongside Miyamoto as director on the 2D Mario games of the 1980s and 90s, agrees: “It is the basic premise of Super Mario games that we can naturally enjoy Mario’s actions. The technical aspects may be different between 2D and 3D games, but this remains the same. If we as players mess up a move because of the controls rather than something we did wrong, then we end up not wanting to play any more. On the other hand, if we feel like things would have worked out if we’d just jumped a little earlier, then that makes us want to try again.”

Mario’s history as a character extends slightly further back than the release of Super Mario Bros in Japan on 13 September 1985. He first appeared in the 1981 arcade game Donkey Kong, trying to rescue a damsel from a giant ape. At this time his name was Jumpman, though Miyamoto’s own name for him was “Mr Video”. It was after some employees at the nascent Nintendo of America noticed a resemblance between the squat, moustachiod character and their warehouse landlord, Mario Segale, that he became known as Mario; Miyamoto liked the nickname, and stuck with it. Another arcade game, 1983’s Mario Bros, was the character’s debut as an Italian plumber, along with his tragically less famous brother Luigi.

The visual limitations of 1980s video game technology – small grids of pixels, a limited colour palette – are the explanation both for Mario’s appearance, with his colour-constrasting blue dungarees and red shirt, and for the trippy aesthetic of Mario games to this day: clouds with eyes, bug-eyed little turtles, animate rocks and trees and mushrooms. “I’ve always designed assets to fit best with the game features – that is to say, so that players could understand them without any explanation, as could people watching from the sidelines,” says Miyamoto.

“There were several reasons why we used pipes [as a visual motif]: they were perfect for the mechanic in Mario Bros, where enemies disappearing at the bottom of the screen would appear again at the top; they had this comic book feel about them where they’d bulge and have something come out of them; and then there was the fact that I would always see them on my way to work [at Nintendo HQ in Kyoto].”

“In the era of 8-bit hardware, a lot of games used black for the background,” adds Tezuka. “However, to create a world where the background would scroll, we made use of these limited colours and came up with a design based on black outlines filled with single colours. Miyamoto drew rough sketches for the Super Mushroom and Super Star, and it seemed perfectly natural to add eyes on to them. After that, it felt like a natural extension to put eyes on the clouds and mountains in Super Mario Bros: The Lost Levels.”

From 1985’s Super Mario Bros until 1996, 2D Mario games became ever more colourful and sprawling, with an ever-expanding store cupboard of vaguely psychedelic power-ups from the classic mushroom to a leaf that bestowed a raccoon tail and ears to a feather that granted Mario the power of flight. In 1996, Mario took his first steps into 3D in Super Mario 64, a breakthrough game that laid out the blueprint for how to move a character around in space. Where most early 3D games are pretty much unplayable now, hampered by the limitations of the nascent technology, Super Mario 64 still feels magical.

Mario owes his current, expanded set of moves to the challenges of running and jumping in 3D, says Yoshiaki Koizumi, who has directed 3D Mario games from Super Mario 64 to Sunshine to Galaxy. “When we moved to 3D for the first time in Super Mario 64 we became acutely aware of how difficult it is to jump on enemies moving in a 3D space,” he explains. “So we created lots of new moves other than jumping that make use of the features of 3D, such as running around or shooting water or spinning … I was full of excitement working with the new technology we had in front of us. I didn’t feel like we were transforming Super Mario into 3D; rather, it was a feeling that we were creating a completely new style of entertainment.” Koizumi later found himself recreating these early experiments during the development of 2007’s Super Mario Galaxy: “There weren’t any other games available where you move around in space with modified gravity, so creating it was a process of trial and error.”

Nintendo’s early experiments with Mario in 3D left Miyamoto unsatisfied. Plans to include Mario’s brother Luigi in the game so that people could play together were swiftly abandoned. “When we tried running our experiments with 3D on a console, Mario was the only thing that moved. Of course there was no background, either. While we’d expected things to be limited, what we ended up with was even less than we anticipated. It was at that point that we gave up on having Mario and Luigi appear at the same time and decided instead to rework the gameplay,” he says.

The famous opening screen of Mario 64, where players can grab and twist a giant Mario face into amusingly grotesque expressions, was also borne of the frustrations and challenges of working in 3D, says Tezuka. “I wasn’t involved in the game design for Super Mario 64, but because it was 3D there were lots of things we were dealing with for the first time. While we were struggling with that, Mr Miyamoto said that he wanted to make it so that players could play outside of the game itself with the model of Mario’s head that a programmer made; letting them rotate it, or pull its nose.”

Around the time that Super Mario 64 was in development, Miyamoto took up swimming and became very enthusiastic about it – if you’ve ever wondered where Mario’s idiosyncratic breaststroke comes from, now you know. Mario’s other designers through the years have taken inspiration from their real-life experiences, too. “Through Mario I wanted to recreate the experience of a hero jumping from rooftop to rooftop like those heroes I saw in my childhood,” says Koizumi. “I achieved this somewhat in Super Mario Sunshine in that you can climb on the rooftops in the plaza and run around. The water-based play with FLUDD [Mario’s water-gun backpack] also reflects my childhood experiences, playing in water and enjoying the coolness on my skin.”

Kenta Motokura, director of the most recent Mario games Super Mario 3D World and Super Mario Odyssey, is part of a generation of Nintendo designers who grew up with the earlier Mario games – and so his approach to the series is informed by his childhood experiences. “Super Mario Bros 3 is my favourite Mario title,” he says. “The idea of having lots of different Kingdoms in Super Mario Odyssey came from Super Mario Bros 3. The fact that I was raised playing Mario games in my childhood had a big impact on how I make games.

“I’ve also used knowledge of body movement, which I’ve gained through sports like snowboarding, as a reference for Mario’s moves, and I’ve included terrain and environments I’ve found interesting in the games as well. I think you can also see things from trips to places such as Mexico or New York that I found fun or that made me nervous reflected in Super Mario Odyssey, too.”

The first level of Super Mario Bros, 1-1, is today regarded as such a perfect example of game design that it is taught at universities. The elements are laid out in such a way that you can’t fail to learn the rules: you have to jump over a Goomba to avoid it; eating mushrooms makes Mario transform; ? blocks contain surprises. Every Mario game has embraced this philosophy of design, where the levels themselves teach you how to play, always giving you a chance to experiment before letting you fail, allowing you to follow your curiosity. It’s that playfulness and experimentation that new generations of Mario designers are encouraged to embrace.

“I tell them first of all they need to have an idea in their mind of how users are going to play,” says Tezuka. “Imagine that we will come running down a particular route, encounter an enemy and dodge them – then we’ll probably wonder about what’s up there on the left and want to go down that way, so there’s where we should put a hidden block. That kind of thinking. It’s like playing pretend, as a child.”